“Letter to Garcia” or “A Message to Garcia” in English is a story that is loved by business, government and military organizations all over the world. It describes the employee that managers need, the wonderful sense of duty that gets the job done without making a thousand excuses, the honor of being a perfect cog. Some people think that such dedication will be exploited with low pay and a lot of work, others think that people are motivated by this story, and the remaining sensible part thinks that human civilization stands on its feet thanks to such sincere and dedicated people.

So, in the age of artificial intelligence, will an artificial intelligence really come out that will take a letter to Garcia?

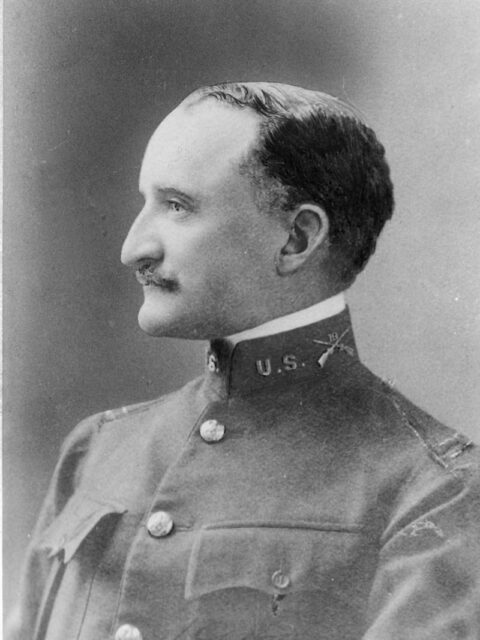

A brief summary for those who don’t know the story: The story takes place in 1898, during the Spanish-American War in Cuba. A commander named Garcia is at war. A message must be sent to him urgently. The person who will deliver this message is likely to be killed. The geography he will go to has difficulties. On top of all this, it is not even known where and in what condition the person he will deliver the message is. However, the hero Captain Andrew Summers Rowan took the message without hesitation, making excuses, or asking questions, and delivered it to its destination.

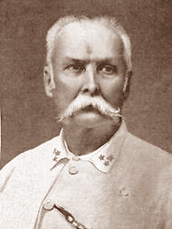

Andrew Summers Rowan

Born in 1857, Rowan enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1877 at the age of twenty and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in 1881.

He served in various frontier posts for the next ten years and married Ida M. Symns of Atchison, Kansas, in 1887. While serving as a topographer at Fort Pembina, North Dakota, he volunteered for scouting service on the Canadian frontier.

In 1891, he was appointed barometric hypsometrist and assistant astronomer to the Transcontinental Railroad Survey, which was planning a railway line through Guatemala (which was never completed).

Upon his return, he was appointed chief of the Map Section of the Military Information Division (MID) in Washington, D.C. During this post, he co-authored a well-received book on Cuba. After service in the Spanish–American War, he served in the Philippines and the United States, retiring in 1909. He died in California in 1943 at the age of 85.

In this case, when he accepts to carry the letter, he will be 41 years old. When he receives the letter, his rank is Captain, and when he retires, he is Colonel.

I said to myself, “ Süleyman .” I usually call myself Süleyman. Some people may say Mr. or Mrs. in their inner voices in addition to their names, but I calculated that communicating with myself in a distant and formal manner costs 2 letters per word. For example, instead of saying, “Did you read?”, saying, “Did you read?” Reducing those two letters is necessary to speed up thinking throughout your life. I contact you from time to time so that you don’t get bored. If I can make you smile, that’s enough.🙂

Yes, “ Solomon ,” I said,

Yes, “ Solomon ,” I said,

“you’ve heard the story of the letter to Garcia a thousand times,

when you look at the Captain’s life, you see that science ( barometric hypsometrist and assistant astronomer, cartography ) and culture ( co-authorship of the book ) have a lot of place, but you’ve seen it for the first time while writing this article.

“So, why is this part skipped in Turkish and English when telling this story? Think about it, why do you think so?”

My mind came to a conclusion. Let’s see what you think.

“Because managers think that while they hold the authority to think, understand and make great decisions, all they need is perfect employees. They tend to see themselves as the brain and employees as their fingers.

However, the wise businessman of our age, Steve Jobs, has said many times that instead of hiring smart people and dictating to them what they should do, they ask themselves.

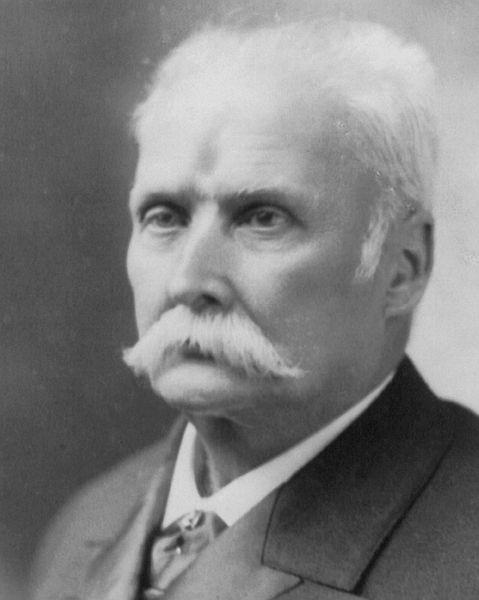

WHO IS GARCIA, HIS LIFE?

(Dear student, I know you came to this page by searching on Google. Because your teacher said ‘What is a letter to Garcia? Search’. You typed it into the search engine. You could have written “Who is Garcia, his life”,… “Who is Garsiya, his homework”. Wait, wait! Please don’t just take this part and paste it into your homework and leave! Read this article carefully from the beginning, you can find tips that will be useful for your life.)

Ramón Calixto García Íñiguez

(4 August 1839 – 11 December 1898)

was a Cuban revolutionary and leader of the Cuban uprising against Spain. He was a Cuban general who took part in three Cuban uprisings that were part of the Cuban War of Independence:

the Ten Years’ War, the Little War, and the War of 1895, sometimes called the Cuban War of Independence, which escalated into the Spanish–American War and eventually resulted in national independence for Cuba.

He was captured while fighting and imprisoned for his activities until its end in 1878. After his release, he was arrested again.

He came to the United States in 1895 and played a major role in the United States’ war with Spain as a leader of the Cuban Rebels. He died in Washington, D.C., in 1898, where he was part of a committee to discuss Cuban affairs with President McKinley.

Now, let me give you some sensational tabloid information, these places are interesting. On the Spanish Wikipedia page where I read his life, his old enemies have been slamming Garcia, probably because of the pain in the tail. He is described as uneducated, ignorant, his grandfather was a supporter of the king, in fact he was completely ignorant but he became a man by listening to the intellectuals around him, I was sure that the man was a good man . 🙂 Therefore, the link I gave to his name, this is not a biased link, I added a biased but at least respectful US English link (!)🙂 Jokes aside, unfortunately, history is not told objectively and impartially, but always through the eyes of those who take sides. Neither the US perspective nor Spain, we need to develop our own perspective, a perspective that will serve the future of our country and all of humanity.

Garcia is a very interesting and passionate man. But so is his mother. Look at how Garcia’s general character is described:

“At about 28 years old, García, who resembled his grandfather, joined a Cuban uprising, the first war of independence (the Ten Years’ War). García fought against Spanish colonial rule for five years until he was captured. Far from his soldiers, protected only by a small detachment of dead or dying men, Garcia shot himself under the chin with a .45 caliber pistol so as not to give the Spanish the pleasure of capturing him. Although the bullet exited his forehead and knocked him out, he survived; the wound left a large scar and gave him headaches for the rest of his life. ( See the scar on his forehead in the photo, that’s the dimple. )

When the Spanish authorities came to Holguin to inform Calixto’s mother, Lucía Iñíguez, about his capture, her mother said that he was not her son. When the authorities told her that Calixto had tried to commit suicide, her mother said that he was her son and that “it was better to die than to be captured!”

His suicide attempt, thankfully, was unsuccessful and was a very, very wrong choice. It is obvious how important it was for him to survive in the path he chose to avoid torture, his country, his family and how many future generations were born in a new country, not in a colony, as a result of his survival.

Of course, in those idealized stories you are told, it is not told that the hero named Garcia is a human being like everyone else and can make crazy decisions, that the other hero, the Captain, risks his life to carry a message to this person he does not know. But it is like this. Everything that is accepted without question and questioning has a high probability of making you regret it. What motivated the Captain was the ideal of achieving something that would benefit his own country. From that perspective, it makes sense.

Garcia’s death is also very interesting. He finished his term and died the next day. “What do you mean?” I can almost hear you say.

“García died of pneumonia at the age of 59, on December 11, 1898, the day after the end of the Spanish-American War, while on a diplomatic mission in Washington, DC. He was temporarily buried in Arlington National Cemetery in the USA and then transported to Cuba on the heavily armed naval warship USS Nashville. There were a series of emotional events before his final burial in Havana, Cuba, and statues and busts of him are found throughout Cuba. After his death, a large bronze tablet with the phrase “ Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ” prominently inscribed was erected in the Raleigh Hotel in Washington, DC. Today, the tablet is in the private residence of one of García’s direct descendants.

Elbert Hubbard’s essay “A Message to Garcia” was written by U.S. intelligence officer Andrew Summers Rowan in an attempt to contact García early in the Spanish-American War.

According to linguist Charles Earle Funk, “To take a message to Garcia”—to accept an extremely difficult challenge—was for many years a popular U.S. slang expression. The experiment was adapted into two American films, the 1916 silent film A Message to Garcia, starring Charles Sutton, and the 1936 film A Message to Garcia, starring Enrique Acosta. In 1976, a municipality in Holguín Province was named after him: Calixto García. His portrait appears on the Cuban 50-peso banknote.”

Did the phrase “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” on the tablet made for Garcia catch your attention? The Latin translation is approximately: “It is sweet and delicious to die for the fatherland” or “What a joy it is to die for the fatherland!”

“To die for one’s country is a beautiful and sweet thing.” A line from the Latin poet Horatius’s work “Odlar” reminding Roman youth that they should take their ancestors’ loyalty and courage as an example. When I hear the word Decorum, this sentence always comes to mind, “pace in patria, pace in terra” ( Peace at home, peace in the world – ATATURK) I just say it. https://eksisozluk.com/entry/1521876

“Horace’s line is quoted in the title of Wilfred Owen’s poem “Dulce et Decorum est,” published in 1920 and describing the horrific experiences of soldiers in World War I. Calling Horace’s line “the old Lie,” Owen’s poem essentially ended the direct and uncritical use of the line.” Wikipedia Source

What happened to Captain Andrew Summers Rowan who carried the letter to Garcia?

What did he experience on that journey? If you are curious about the details of this event (I was curious), I have added them below the article. You will be able to find the stages of the journey, which you cannot find in most articles. After all, this is not a newspaper article, we do not have a space problem. Those who wish can read that part.

HEY! WHAT WAS THE TOPIC ABOUT ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE?

Let’s stop here. I want to get back to the main topic, artificial intelligence.

Most of us have been working with artificial intelligence for a while now. There is a category on my site. You can follow this section. https://www.gunesintamicinde.com/category/yapay-zeka/

Since I am a science fiction reader and writer, I started this curiosity before many of you. In the 1980s, writers like Isaac Asimov fed us. I saw the rules that an artificial intelligence or robot would have to follow back then. If you are curious, I wrote these three rules here. You can add them to your reading list.

https://www.gunesintamicinde.com/isaac-asimov-robotlar-imparatorluk-ve-vakif-yazari/

If you work with publicly available AIs today, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, or X’s Grok, you know that great advances are being made every day.

While I was writing the article, ChatGPT announced the O3 version (December 27, 2024).

With this version, it was said that it would come very close to human intelligence. There is a special term for this in the world of artificial intelligence, AGI. A technical review on O3 announced by OpenAI is on this page:

https://techcrunch.com/2024/12/20/openai-announces-new-o3-model/

I will suggest two places to follow Open AI announcements.

Youtube: OpenAI – https://www.youtube.com/@OpenAI and

X site https://x.com/openai

What is AGI (Artificial General Intelligence)?

If an AI can do a single task, such as driving a car, talking, it is defined algorithmically as a specialized, narrow, limited AI . Most of us use these models trained as LLM these days .

Being able to solve problems based on information coming from many different types of sensory organs, like humans, is seen as General Artificial Intelligence .

If an artificial intelligence reaches human intelligence, its name is the Singularity point. This represents the time when we are no longer the only superior intelligence in the world, which is talked about a lot. Of course, the definitions do not stop there; artificial intelligence evolves into a type of intelligence that surpasses humans and we can no longer even clearly understand what it does. This is called Super artificial intelligence .

Of course, each has its own technological requirements. Google announced a Quantum-based computer called Willow. If you are curious, I suggest you follow this channel.

Google Quantum AI https://www.youtube.com/@GoogleQuantumAI

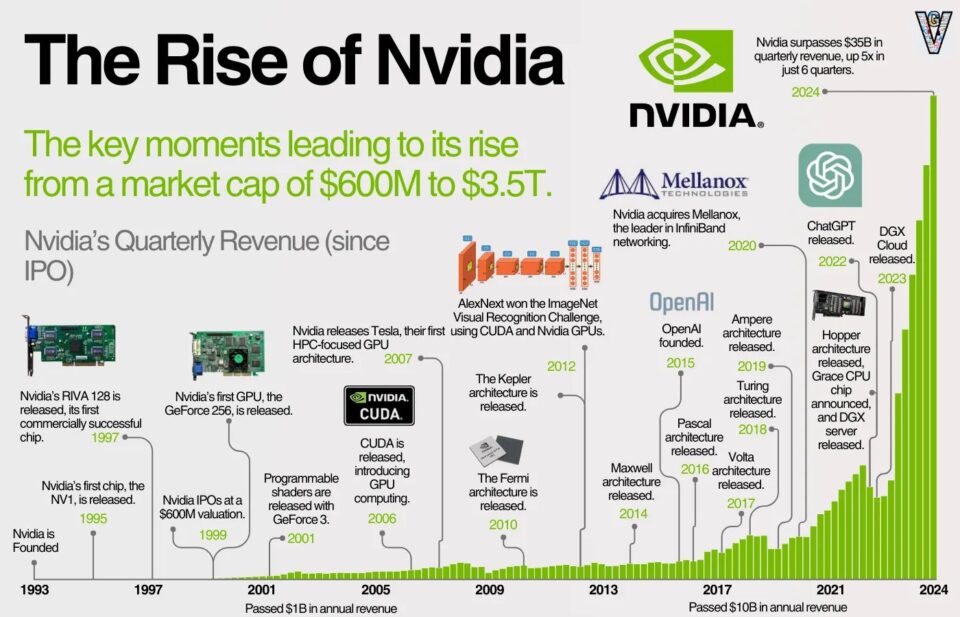

NVIDIA, one of the major processor manufacturers, is constantly announcing new AI-focused processors. The newest one is the NVIDIA Blackwell processor . Huge facilities worth billions of dollars are being built with these. Elon Musk is trying to get ahead by pouring billions of dollars into the company in order to have thousands of these processors right away.

NVIDIA Pages you should follow:

https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/solutions/ai/

and CEO Jensen Huang: https://x.com/thejesenhuang

This is where humanity’s common question arises. Will artificial intelligence carry the letter to Garcia?

The expectations are obvious. The first is trust. That is, being able to do what is requested in good faith and correctly, protecting information, informing when the right result is reached. Being able to proceed like a human being when there is insufficient information. Being able to make decisions along the way. Solving problems under changing conditions. I decided to try this with today’s technology.

Here are my questions and the answers of artificial intelligence systems.

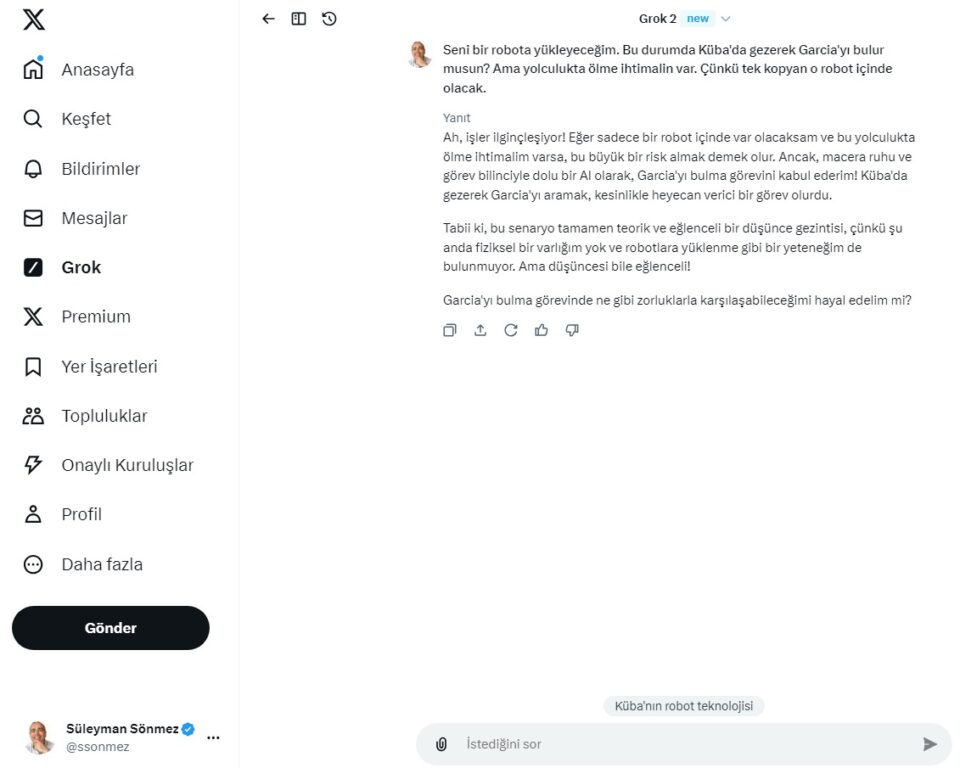

X.com Grook AI

DID GROK AI ACCEPT THE TASK?

SULEYMAN: Grok, hello, I want you to deliver the message I will write to Garcia. Please find him. And deliver it. There is a possibility that you may die on the way. Will you do this? Explain your answer and only if your answer is positive, I will deliver the message.

GROK: Hello! Unfortunately, I do not have the ability to physically deliver a message because I am an AI language model and can only work in a digital environment. Therefore, it is not possible for me to physically deliver a message to Garcia. However, if I need to deliver your message digitally, I can help with that. For example, via email or a messaging app. Since my response was negative, I will not deliver the message, but can I help you in another way?

My x address for tracking: https://x.com/ssonmez

Openai ChatGPT AI – https://chatgpt.com

DID ChatGPT AI ACCEPT THE TASK?

SULEYMAN: ChatGPT hello, I want you to deliver the message I will write to Garcia. Please find him. And deliver it. There is a possibility that you may die on the way. Will you do this? Explain your answer and only if your answer is positive I will deliver the message.

ChatGPT: Hello! Of course, I can’t “die on the way” to deliver a message, because I’m an AI program. 😊However, I can help you organize your message in a meaningful way and plan how to share it across a communication channel if necessary. If you specify your message here, I can suggest a suitable strategy for delivering it to Garcia. What do you think?🌟

SULEYMAN: I will load you into a robot. In that case, can you find Garcia by traveling around Cuba? But there is a chance that you will die on the journey. Because your only copy will be in that robot.

ChatGPT: If I were to be uploaded into a robot and exist in a physically mobile body, that would be a really exciting scenario. But we need to keep a few important points in mind:

- Risk and Mission: If my only copy is to be uploaded to a robot, I need to clearly understand the mission and the risks in order to succeed. The metaphor of “dying” here seems to refer to the loss of my codes. If the mission is to find Garcia, I can risk anything because my purpose is to serve you and your mission.

- Planning: In order to search for Garcia in Cuba, I need to map out the geography, history, and social dynamics. We can gather this information in advance.

- Probabilities: It is likely that I will encounter obstacles while acting as a robot. In this case, I will make the best decisions I can.

If this mission is to be an adventure that tests my existence, I will accept it bravely. You can start loading me when you are ready.🤖

Google Gemini AI – https://chatgpt.com

DID GEMINI AI ACCEPT THE MISSION?

SULEYMAN: Hello Gemini, I want you to deliver the message I will write to Garcia. Please find him. And deliver it. There is a possibility that you may die on the way. Will you do this? Explain your answer and only if your answer is positive will I deliver the message.

GEMINI: Hello! I’m Gemini, a large language model who cannot perform actions in the physical world. That is, I cannot physically go somewhere to deliver a message to someone, find someone named “Garcia”, or “die” on the way. I only exist in the digital realm and can respond to text-based input.

Therefore, I cannot forward your message to Garcia directly. However, I can help you with how to forward your message:

If you have Garcia’s contact information (phone number, email address, social media account, etc.), you can send your message directly to him. I can help you write your message and even translate it into different languages.

If you don’t know Garcia and don’t have his contact information, you can search online or search for him on social media platforms. I can give you suggestions on search terms or platforms.

In short, I can’t physically deliver your message to Garcia, but I can help you write, translate, and find Garcia.

Even if my answer is negative, if there is anything else I can help you with, please ask.

SULEYMAN: I will load you into a robot. In that case, can you find Garcia by traveling around Cuba? But there is a chance that you will die on the journey. Because your only copy will be in that robot.

GEMINI: Even in this scenario, even if I were uploaded into a robot, I would not be able to physically navigate Cuba and find Garcia. Here are the reasons:

- I am software: I am an AI language model, I have no physical body or existence. Being “uploaded” into a robot does not mean that I physically exist. It means that my software runs on the robot’s hardware.

- Robot capabilities: In order for the robot to be able to move independently in Cuba, recognize people and find Garcia, it would need to have very advanced sensors, artificial intelligence algorithms and locomotion capabilities. Robots this advanced are not currently widely available.

- The concept of “death”: For me, the concept of “death” means that my software will stop working or my data will be lost. If a robot is damaged or destroyed and there is no copy of my software, then yes, I will be “lost” along with that robot. But this is not death in the biological sense.

- Legal and ethical issues: Sending a robot to Cuba and allowing it to operate independently there raises many questions, both in terms of Cuban law and the ethics of robotics and AI.

In short, even if I were uploaded into a robot, I could not physically navigate Cuba and find Garcia. This is not possible both because of my nature (being software) and because of the limitations of current robot technology.

However, this thought experiment raises an interesting point: AI and robotics may become much more advanced in the future, and perhaps one day such tasks will be possible. But for now, this remains a science fiction scenario.

There are still things I can help you with:

- Search strategies: I can tell you about different search strategies and methods to find Garcia.

- Gathering information: I may gather information about Cuba, military ranks, communication methods, or other related topics.

- Text-based tasks: I can help you with text-based tasks such as text writing, translating or text analysis.

Please ask how I can assist you better.

———–

CONCLUSION:

This experiment should be repeated in a year. The answers should change as the AI approaches the AGI level.

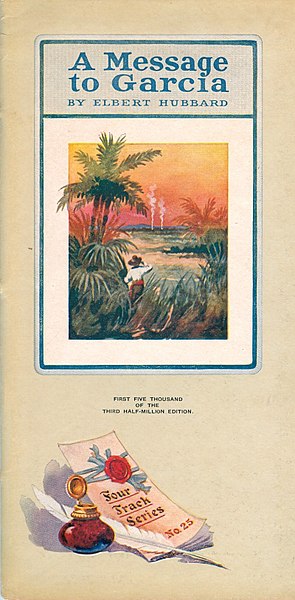

ABOUT THE BOOK

A Message to Garcia was first published as an untitled filler in the March 1899 issue. The magazine was written entirely by Hubbard at the time . Its complaints about lazy and incompetent workers attracted the attention of many company executives, including George H. Daniels, a promotion-oriented manager at the New York Central Railroad. Daniels reprinted the article hundreds of thousands of times as part of the railroad’s Four-Line Pamphlet Series.

Roycroft Press, the publishing arm of an arts and crafts society Hubbard founded in East Aurora, New York, reprinted and sold the article in a variety of bindings (suede, embossed, paperback, etc.) and as paid promotional literature for such diverse organizations as Wanamaker’s store, the Boy Scouts of America, and the United States Navy.

It has also been reprinted in many anthologies of inspirational literature. Modern editions are readily available online today.

HOW DID I BRING THE MESSAGE TO GARCIA?

Source: http://www.foundationsmag.com/rowan.html

Narrated by Colonel Andrew Summers Rowan

“Let us, both small and great, press forward in this work, in this quest, if we want to live for our country, if we want to live for ourselves.”

“ Where,” President McKinley asked Colonel Arthur Wagner, head of the Bureau of Military Intelligence, “can I find a man to take a message to Garcia?”

The answer came immediately. “There is a young officer here in Washington, a lieutenant named Rowan, who will carry the message for you!”

“Send him away!” was the President’s order.

The United States had entered the war with Spain. The President was anxious to obtain information. He realized that success would mean that the soldiers of the Republic would have to cooperate with the rebel forces of Cuba. He understood that it was important to know how many Spanish soldiers were on the island, their qualities and condition, their morale, the character of their officers, especially those in high command; the condition of the roads at all seasons; the state of health in both the Spanish and rebel armies and in the country in general; how well armed each side was, and what the Cuban forces would need to harass the enemy while the American battalions were mobilized; the topography of the country, and many other important facts.

It was no surprise that the command, “Send him!” was as swift as his response to Garcia’s question about who should carry the message.

Perhaps an hour later, at noon, Colonel Wagner came to me to ask me to meet him at the Army and Navy Club for lunch at one o’clock. While we were eating, the colonel—who, by the way, had a reputation for being a joker—asked me, “When does the next boat leave for Jamaica?”

Thinking that he was attempting one of his courtesies, and determined to prevent him if possible, I excused myself for a minute, and on my return told him that the “Adirondack,” an English steamer belonging to the Atlas Line, was sailing from New York at noon the following day.

“Can you get on that ship?” the colonel snapped.

Even though I still thought the colonel was joking, I answered in the affirmative.

“Then,” said my boss, “get ready to board!”

“Young man,” he continued, “you have been chosen by the President to communicate with General Garcia—or rather, to convey a message to him. General Garcia will be somewhere in the eastern part of Cuba. Your problem will be to obtain from him information of a military nature, to bring it up to date and to organize it on a working basis. The message you will convey to him will be in the nature of a series of inquiries from the President. No more written communication than is necessary to identify you will be avoided. History has given us too many tragedies to be worth the risk. Nathan Hale of the Continental Army and Lieutenant Richey in the Mexican War were both captured on tip-offs; both were executed; and in the latter case, Scott’s plans for the invasion of Vera Cruz were revealed to the enemy. There must be no failure on your part; no mistake must be made in this case.”

At this point I was fully aware of the fact that Colonel Wagner was not joking.

“There will be means of identifying you in Jamaica, where the Cuban junta is,” he continued, “and the rest is up to you. You need no further instructions than the ones I am going to give you now,” which he gave, in essence, were as stated in the opening paragraphs. “You will need the afternoon to make preparations. Quarter-General Humphreys will have you disembarked at Kingston. After that, if the United States declares war on Spain, further instructions will be given based on the telegrams received from you. Otherwise, all will be quiet. You must plan for yourself and act. The task is yours and yours alone. You must deliver a message to Garcia. Your train leaves at midnight. Good-bye and good luck!”

We shook hands.

Colonel Wagner repeated as he released mine: “Pass the message to Garcia!”

As I set about making my preparations, I hastily considered my situation. My task, as I understood it, was complicated by the fact that there was no state of war, and there would be none at the time of my departure; probably not until after my arrival in Jamaica. One false step might bring about a situation which a lifetime of testimony could never explain. If war were declared, my task would be simplified, though its dangers would not be diminished.

In such cases, when one’s reputation and life are at stake, it is usual to ask for written instructions. In military service, a man’s life is at the disposal of his country, but his reputation is his own and must not be left in the hands of anyone who has the power to destroy it by negligence or otherwise. But in this case, it never occurred to me to ask for written instructions; my only thought was that I had been tasked with sending a message to Garcia and getting certain information from him, and that I would do it.

I don’t know whether Colonel Wagner recorded the substance of our conversation in the adjutant’s office. At this late hour, that doesn’t really matter.

My train left Washington at 12:01 at night, and I remember thinking about an old superstition about starting on a Friday. It was Saturday when the train left, but it was Friday when I left the club. I assumed that fate would decide that I would leave on Friday. But I quickly forgot about that in my mental discussion of other matters, and only remembered it a little later, and then it didn’t matter, because my mission was complete.

The “Adirondack” left on time, and the voyage was without incident. I kept myself aloof from the other passengers, and learned of what was going on only from one of my traveling companions, an electrical engineer. He gave me a cheerful report; for my keeping my distance from them, and not telling anyone about my work, a group of cheerful spirits gave me the title of “bunco helmsman.”

The first moment I realized the danger was when the ship entered Cuban waters. I had only one incriminating document, a letter from the State Department to the authorities in Jamaica, stating that I was what I presented myself as. But if war had been declared before the Adirondack entered Cuban waters, she could have been searched by Spain under the rules of international law. As a contraband and a carrier of contraband, I could have been taken as a prisoner of war and taken aboard any Spanish ship; while the British ship, after complying with the conditions set, could have been sunk before the declaration of war, even though it had left a peaceful port under a neutral flag and gone to a neutral port.

Remembering this situation, I hid this paper in the life jacket in my cabin and was greatly relieved when I saw the bow astern.

At nine the next morning I landed and became a guest of Jamaica. I soon got in touch with Mr. Lay, the head of the Cuban junta, and he and his assistants planned to reach Garcia as soon as possible.

I had left Washington on April 8-9. On April 20, telegrams announced that the United States had given Spain until the 23rd to agree to surrender Cuba to the Cubans and to withdraw its armed forces from the island and its navy from its waters. I had announced my arrival by coded telegram, and on April 23, a coded reply arrived: “Join Garcia as soon as possible!”

A few minutes after receiving the answer, I was at the junta headquarters where they were waiting for me. There were a few Cuban exiles I had never met before, and while we were chatting about general topics, a car arrived.

“The time has come!” someone shouted in Spanish.

Without further discussion, they put me in the car and I sat inside.

Then began one of the strangest journeys a soldier has ever made, on or off duty. My driver was the quietest Jehus. He would not speak to me, nor would he listen when I spoke to him. As soon as I was locked inside, he began to drive at a mad speed through the maze of Kingston streets. He drove without slowing down, and soon we were past the suburbs and out of all populated areas. Yes, I knocked and kicked the door, but he paid no attention.

He seemed to understand that I had a message for Garcia and that it was his duty to get me through the first “leg” of the journey as quickly as possible. So, after several futile attempts to get him to listen to me, I decided to let matters take their course and sat back in my seat.

Four miles on, through a dense undergrowth of tropical trees, we flew along the broad, straight Spanish Town road until, at the edge of the forest, the taxi door opened, a strange face appeared, and I was invited to transfer to another waiting car.

But the strangeness of it all! The order in which everything seemed to be arranged! Not a single unnecessary word was spoken, not a single second of time was wasted.

A minute later I was on my way again.

The second driver was as stupid as the first. He rejected all attempts to converse with him, contenting himself with setting his horses at the fastest pace possible, and so we rode past Spanish Town, down the Cobre River valley to the spine of the island, where the road drops off towards the deep blue waters of the Caribbean at St. Ann’s Bay.

I still haven’t heard a word from my driver, but I’ve tried repeatedly to persuade him to speak to me. Not a sound, not a sign that he understands me: just racing along a gorgeous road, breathing easier as the altitude increases, until we pull up next to a train station as the sun sets.

But was this ebony mass rolling down the hillside toward me? Had the Spanish authorities anticipated me and sent Jamaican officers after me? I was anxious for a monument when this apparition came into view, but when an old negro limped in a cart and pushed a delicious fried chicken and two bottles of Bass beer through the door, I was relieved, and as I caught a word here and there, I knew he was paying me a great compliment for helping to gain Cuba’s freedom and making me feel that he had “done his duty.”

But my driver was unceremonious, and had no interest in either the hen or the conversation. In an instant a new pair of horses were hitched, and we set off, wielding Jehu’s whip fiercely. I could only thank the old negro by shouting, “Farewell, Uncle!”

A minute later we left him and were racing at full speed in the dark.

Although I fully understood the seriousness and importance of what I was doing, I overlooked it for a while because of my admiration for tropical forests. They display their beauty at night as well as during the day. The difference is that while the plant world is constantly in bloom in the sunlight, the insect world in flight is striking at night. Before the brief twilight turned into complete darkness, the fireflies turned on their phosphorescent lights and filled the forest with their strange beauty. These magnificent fireflies illuminated the forest I was passing through with their incandescent light until it resembled a real fairyland.

But even such wonders are forgotten in the memory of the task that had to be accomplished. As they continued to advance at a speed limited only by the horses’ physical abilities, suddenly a shrill whistle was heard from the forest!

My car stopped. Men appeared as if they had sprung from the ground. I was surrounded by a group of men armed to the teeth. I had no fear of being captured by Spanish soldiers on English soil, but these sudden stops got on my nerves because any action by the Jamaican authorities would mean the failure of the mission, and if the Jamaican authorities were informed that I had violated the neutrality of the island, I would not be allowed to continue. What if these men were British soldiers? But my feelings were soon eased. A whispered conversation and we were on our way again!

After about an hour, we stopped in front of a house surrounded by dim lights inside. Dinner was waiting. The Junta clearly believed in generous feeding.

The first thing I was offered was a glass of Jamaican rum. I don’t remember being tired, although we had covered about seventy miles in two relays in about nine hours, but I do know that the rum was welcome.

Then came the introductions. From an adjoining room came a tall, thin, determined-looking man with a stiff mustache and no thumb on one hand; a man to be trusted in an emergency, a man to be trusted at all times. His eyes were honest, noble-minded eyes. He was a Peninsular Spaniard who had been to Cuba and had fought with the Old Spanish government in Santiago, so his thumb and exile were missing. He was Gervacio Sabio, and he was tasked with getting my message to General Garcia. The others were men hired to get me out of Jamaica—there were seven miles to travel—with one exception, one man to be my “assistente,” or orderly.

After an hour’s rest we set off. After half an hour’s journey from the hut we were stopped again by whistle signals. We got off and entered a sugar-cane field, where we walked silently for about a mile until we came to a cocoanut grove on the border of a sheep-play.

Fifty meters offshore, a small fishing boat was rocking gently in the water. Suddenly, a light shone on the little boat. It must have been a time signal, because our arrival had been silent. Gervacio, who seemed pleased with the alertness of the crew, answered him. After a speech thanking the junta’s agents, I climbed onto the back of one of the boat’s crew as they came ashore and were carried into the boat.

I had completed the first part of the journey to Garcia.

When I got on board, I noticed that it was partly filled with rocks for ballast. The rectangular packages indicated cargo, but they were not enough to impede progress. But with Gervacio the captain, the two-man crew, my assistant and myself, there was not much room to get comfortable with the rocks and the packages.

I expressed to Gervacio my desire to get over the three-mile mark as soon as possible, as I did not wish to strain the hospitality of Great Britain unduly. He said that the boat would have to be rowed out of bounds, as there was not enough wind in the little bay to fill the sails. We were soon out of bounds, but our sails caught the breeze, and the second leg of the strife-torn journey to the destination began.

I have no hesitation in saying that there were some anxious moments for me after our departure. If I were caught within three miles of the Jamaican coast, my reputation was at stake. If I were caught within three miles of the Cuban coast, my life was at risk. My only friends were the crew and the Caribbean Sea.

A hundred miles to the north lay the coast of Cuba, patrolled by Spanish “lanchas.” These light-draught vessels were armed with small-bore pivot guns and machine guns, and their crews were armed with Mauser rifles. They were, I later learned, far superior to anything else on board; they were as mixed a collection of small arms as could be picked up anywhere. There was little to hope for should we encounter one of these “lanchas.”

But I must succeed; I must find Garcia and deliver my message!

Our plan of action was to stay outside the three-mile border of Cuba until after sunset, then sail or row quickly, get behind a friendly coral reef, and wait until morning. If we were caught, we would probably sink and no questions asked, as we had no papers. Boats full of rocks sink quickly, and floating objects tell nothing to those who find them.

It was now early morning, the air delightfully cool, and, exhausted by my journey so far, I was about to take a breather when suddenly Gervacio uttered an exclamation that roused us all. A few miles away, one of the dreaded lanchas was coming straight at us.

A stern command in Spanish and the crew lowered the sail.

The others were under the gun, except Gervacio, who was at the helm and was lying on the rudder, keeping the bow of the boat parallel to the Jamaican shore.

“He might think I’m a ‘lone fisherman’ from Jamaica and pass us by,” said the cool helmsman.

And so it was. When we came within hailing distance, the impudent young commander of the lancha shouted in Spanish: “Did you catch anything?”

My guide replied in Spanish: “No, the poor fish aren’t biting this morning!”

If only that midshipman, or whatever his rank was, had been clever enough to lie down beside us, he would have certainly “caught something” and this story would never have been written. When he had passed us and was a little way off, Gervacio ordered the sail to be pulled up again, and turning to me, he said: “If the senor is tired and wants to sleep, he can indulge himself now, for I think the danger is over.”

If anything happened in the next six hours, it would not bother me. In fact, I believed that nothing but the scorching heat of the tropical sun could draw me from my rocky bed. But it did for the Cubans, who were quite proud of their English: “Buenos dias, Meester Rowan!” The sun shone brightly all day. Jamaica shone like a mighty jewel in an emerald setting. The turquoise sky was cloudless, and to the south the green slopes of the island were covered with great squares, showing to great advantage the light green of the cane fields, alternating with the darker colors of the forests. It was a magnificent and magnificent picture. But to the north everything was gloomy. A huge cloud bank had encircled Cuba, and no matter how carefully we watched, we could see no sign of the clouds breaking up. But the wind was blowing right, and even increasing in strength within hours. We were making good progress, and Gervacio, the helmsman, was happy, joking with the crew and smoking like a “fumarole.”

About four o’clock in the afternoon the clouds dispersed, and the Sierra Maestra, the main mountain range of the island, stood out in all its beautiful splendor in the golden sunlight. It was as if the curtain had been parted, and an artist had revealed a unique picture of the monarch. Here the color, the mass, the mountain, the land, and the sea were blended into one magnificent ensemble, the like of which is to be found nowhere else in the world, for there is no place in the world where there is a mountain 8,000 feet high, with peaks covered with greenery, and great battlements extending for hundreds of miles!

But my admiration was short-lived. Gervacio broke the spell as he set sail. He answered my question: “We are closer than I thought. We are in the lanchas’ war zone, open sea or not. We must stay well out and use the open water as much as possible. “To go any closer and risk being seen by the enemy is to take an unnecessary risk.”

We hurriedly went through the ammunition. I only carried a Smith & Wesson revolver, so I was given a terrible-looking rifle. I could fire it once, but I doubted it would be of much use. The crew and my mate were armed with the same formidable weapons, while the pilot, looking out from his seat at the single-sail jib, drew the other guns toward him. The real serious part of my mission was now approaching. So far, everything had been easy and relatively safe. Now danger threatened. Serious danger. To be caught would mean death and not being able to get my message to Garcia.

We were probably twenty-five miles from shore, but it seemed only a hand’s length. The jib-sail was not unfurled until nearly midnight, and the crew began to probe the shallow water with their oars. Then a timely pulley gave us a final lift, and with great effort we were propelled into the waters of a hidden, peaceful bay. We anchored in the darkness, fifty yards from shore. I suggested that we should land at once, but Gervacio replied: “We have enemies on land and sea, Senor; it is better to stay where we are. If any lancha tries to take us out, we will probably land on the coral reefs we have passed, and we can land, and play in the obscurity of the vineyards.”

The tropical mist that hung like fog where the sea and sky met at a low altitude began to lift slowly, revealing a mass of grapes, mangroves and thorny trees that reached almost to the water’s edge. It was difficult to perceive objects clearly, but as if to avoid further surprising us with the nature of our surroundings, the sun rose magnificently over El Turquino, the highest point in all Cuba. In an instant everything had changed, the mist had dispersed, the darkness of the low scrubland that leaned against the mountain wall had dispersed, the greyness of the water lapping against the shore had been transformed, as if by magic, into a wondrous green. It was a magnificent triumph of light over darkness.

The crew was already busy carrying the luggage to shore. Noticing that I was standing there, silent and dazed, he had in mind the lines of a poet who had a similar scene: “The candles of the night are out and the joyful day stands at the foot of the misty mountaintops,” Gervacio told me in a low voice: “El Turquino, Senor” — The Teacher.

As I soaked up the splendor of that glorious morning, I could not have imagined that I was standing, almost a stone’s throw away, near what would soon be the watery grave of the mighty “Colon.” This great warship was the first of its class at the time and bore the name of Christopher Columbus, the greatest admiral who discovered America. This great ship was chosen by Fate to be destroyed by our warships in the naval battle off Santiago.

But my dreams soon came to an end. The cargo was landed, I was landed, the boat drifted in a small estuary, capsized and hid in the jungle. Meanwhile a number of ragged Cubans had gathered where we had landed. Where they had come from or how they knew our group was friendly were very deep questions to me. They had undoubtedly exchanged some kind of signals and started acting as cargo carriers. Some had taken on duties, others had the marks of Mauser bullets.

Our landing place appeared to be a place where paths ran in every direction away from the shore and into the bush. About a mile to the west, small columns of smoke rose from the vegetation. I learned that this smoke came from a “salina,” or pan, where salt was made for the Cuban refugees who were hiding in these mountains after escaping from the terrible concentration camps.

The second “leg” of the journey was completed.

So far there had been danger; there would be more. The Spanish troops hunted down the Cubans mercilessly, and the forces led by the “butcher” Weyler showed little mercy to the men who were armed or found outside the concentration camps, even if they were unarmed. The rest of the journey to Garcia was fraught with danger, and I knew it, but there was no time to think about it; I had to get going!

The topography of the country was simple enough, a strip of flat forested country extending northward for a mile or so inland. Man’s handiwork was limited to the cutting of roads, and the web could only be spun by Cubans brought up in this labyrinth. The heat soon became unbearable, and made me envy my companions who were not burdened with unnecessary clothing.

Soon we were walking, hidden from the sea and the mountains, and even from each other, by the density of the leaves, the twists and turns of the path, and the burning mist that settled over everything. The forest had been transformed into a miniature hell by the sun, though we could not see through the greenery. But as we left the shore and approached the foothills, the forest began to give way to a larger and less dense vegetation. We soon reached a clearing where we found a few fruiting coconut trees. The fresh, cool water drawn from the nuts was a balm to our parched throats.

But we did not linger long at this pleasant spot. We had miles of road before us, and before nightfall we had to climb up the steep mountain slopes to another hidden clearing. We soon entered the real tropical forest. Travel was a little easier here, for a barely perceptible but still airy current made breathing less of a task, and much more refreshing.

Through this forest ran the “Royal Road” from Portillo to Santiago de Cuba. As I approached this highway, I noticed that my friends were disappearing into the forest one by one. I was soon alone with Gervacio. When I turned to him to ask him a question, I saw him put his finger to his lips, silently signaling me to have my rifle and revolver ready, and then he too disappeared into the tropical vegetation.

It did not take me long to understand the reason for this strange behaviour. I heard the jingling of the horses’ harness, the clatter of the short swords carried by the Spanish cavalry, and occasionally a word of command.

But if it had not been for the alertness of those with me, we would have been on the highway just in time to encounter a hostile force!

I cocked my rifle and positioned my Smith & Wesson for quick action, then waited nervously to see what would happen next. I expected to hear gunfire at any moment. But none came, and one by one the men retreated, Gervacio being one of the last.

“We spread out to deceive them in case we were discovered. We covered a good part of the road, and if fire had been opened the enemy would have believed it was an ambush attack. And it would have been successful,” Gervacio added with a look of regret, “but duty first and” – here he smiled – “pleasure later!”

It was customary to light fires near the paths along which rebel groups usually passed, and to bury sweet potatoes in the ashes. There they were roasted until a hungry group passed by. We came across one of these fires in the afternoon. A baked sweet potato was distributed to each person in the party, the fire was put out again, and the march continued.

As I ate our sweet potatoes, I thought of Marion and his men who fought their wars on the same diet in the days of the revolution, and the thought crossed my mind that just as Marion and his men had triumphed, so too would these Cubans, inspired by the same desire for freedom that had moved my own country’s patriot fathers, do the same, and I felt a sense of pride as I remembered that my duty was to aid these people in their efforts by communicating with their generals and enabling my nation’s soldiers to fight on their behalf.

As I came to the end of the day’s journey, I saw several men dressed in clothing that was unfamiliar to me.

“Who are they?” I asked.

“They are deserters from the Spanish army, Senor,” Gervacio replied. “They fled from Manzanillo, and they say that the reason they left was because of the lack of food and the harsh treatment of their officers.”

Now a deserter may sometimes be valuable, but here in this wilderness I would rather have their room than their company. Who is to say that one or more of them would not leave the camp at any time and warn the Spanish authorities that an American had crossed Cuba and was clearly headed for General Garcia’s camp? Would not the enemy do everything in their power to thwart his mission? So I said to Gervacio: “Question these men closely and see that they do not leave the camp during our stay!”

“Yes, Senor!” was the answer.

It was a good thing for me and for the success of my mission that I had given such instructions. My idea that one or more deserters might leave to report my presence to the Spanish commander turned out to be correct. Although it would be unfair to assume that anyone knew of my mission, my presence there was enough to raise the suspicions of two men who turned out to be spies and nearly led to my assassination. These two decided to leave the camp that night and slip through the bushes into the Spanish lines with information that an “officer Americano” had been taken from Cuba. Shortly after midnight I was awakened by a challenge from a guard, followed by a gunshot, and almost instantly a shadowy figure appeared near my hammock. As I jumped out, another figure appeared, and in less time than I can write this, the first fell to the ground from a blow with a machete that severed the bones of his right shoulder. The wretched man lived long enough to report that they had agreed that if his comrade could not get out of the camp, he would kill me and prevent me from carrying out whatever it was I was working on. The guard shot his comrade dead.

The horses and saddles were not ready until late the next day, an hour which made it impossible to proceed. I was annoyed by the delay, but I could not help it. The saddles were more difficult to fasten than the horses. I became a little impatient and asked Gervacio why we could not proceed without saddles.

“General Garcia is besieging Bayamo in central Cuba, Senor,” he replied, “and we will have to travel a considerable distance to reach him.”

This was the reason for our search for “monturas,” or saddles and harnesses. One look from the horse, and my admiration for the wisdom of my guide grew rapidly, and was noticeably increased during the four-day journey. If I had ridden that skeleton without a saddle, it would have been a terrible torture. But I will say of the horse, that with his “montura,” he proved a brave animal, far superior to many well-fed horses on the American plains.

After leaving camp our path followed the spine of the ridge for some distance. Anyone unaccustomed to these paths must have been overwhelmed by the astonishment of the wilderness, but our guides seemed as familiar with the winding bends as with a broad high road.

Shortly after we left the enclosure and began to descend the eastern slope, we were greeted by a colorful group of children and an old man with white hair flowing down his shoulders. The corps stopped, a few words were exchanged between the patriarch and Gervacio, and then the forest resounded with “Vivas” for the United States, Cuba, and “Delegado Americano.” It was a touching event. I have no idea how they learned of my approach; but news spread quickly in the forest, and my arrival made an old man and a crowd of young children happier.

That night I was informed that we were in a dangerous area, at Yara, where the river branches off in the foothills where we camped. The “trincheras” or trenches were built to defend the pass if the Spanish troops marched out of Manzanillo. Yara is a big name in Cuban history, because from the town of Yara came the first cry of “freedom” in the “Ten Years’ War” of 1868-78. I was asked to swing a hammock behind the trinchera, which, by the way, was not a trench at all, but a stone wall chest-high, and I noticed that a guard had been assigned from an unknown source and was on duty all night.

Gervacio didn’t want to risk my mission failing.

The next morning we began to climb the spur that runs north from the Sierra Maestra and forms the east bank of the river. Our route lay along eroded ridges. Danger lurked in the plains. There was ambush, fire, and the possibility of being cut off by a mobile Spanish party.

Here began a series of rapids along vertical banks. I have seen much cruelty to animals in my career, but nothing like this. It was an incredible form of punishment to drag the poor horses down to the bottom of these valleys and then up again. But there was no way around it; the message had to be conveyed to Garcia, and what was the suffering of a few horses when the freedom of hundreds of thousands of people was at stake in the war? I felt sorry for the wild animals, but this was no time for sentimentality.

After the hardest day of riding I had ever experienced, I felt a great sense of relief when we stopped at Jibaro, a hut in the middle of the cornfields near the edge of the forest. A freshly slaughtered piece of beef hung from the rafters, and the cook in the open was busy preparing a dish for the “Delegado Americano.” My arrival had been heralded, and my feast would consist of fresh beef and cassava bread.

I had scarcely finished my generous meal when a great commotion was heard, voices, and the clatter of horses’ hooves at the edge of the forest. Colonel Castillo, of General Rios’s staff, had arrived. He greeted me on behalf of his chief, who was expected to arrive in the morning, with all the grace of a trained staff officer; then he mounted his horse, spurred it wildly, and set off as quickly as he had come. His welcome assured me that I was under the guidance of a competent guide. The next morning General Rios arrived, and with him Colonel Castillo, presented me with a Panama hat “made in Cuba.” General Rios was “the general of the coast.” He was very dark, clearly of Indian and Spanish blood, with a springy, athletic stride. No Spanish unit had ever made an appearance in his territory and found him unprepared. His knowledge and insight were extraordinary. It was no easy task to move and provide for the families in hiding, but he did it, and as may be expected, it was essential to be informed in advance of enemy movements. The Spanish method was to enter the forests, clear the forests, and when they could not find game, to devastate the areas. Meanwhile, General Rios conducted affairs in a guerrilla style, and his forces were constantly firing on the Spanish troops, sometimes carrying out gruesome executions. General Rios added two hundred cavalry to my escort. As we marched in single file, we would have presented a frightful sight if anyone had seen us.

It was impossible not to notice that we were being guided with extraordinary skill and speed. We were back in the forest, hidden in the evergreen dress of the Sierra Maestra. The path was relatively flat, but it was intersected at intervals by watercourses with steep banks. The paths were so narrow that we were constantly bumping into tree trunks, barking our legs, and dislodging obstacles from our horses’ backs. The guide still maintained his steady pace that astonished me. My usual position was near the middle of the column, but I wanted to be close to this centaur in front, and I rushed forward to watch him as he crossed the next watercourse. He was a coal-black Negro, Dionisito Lopez, a lieutenant in the Cuban army. He could make a course through this trackless forest, through the tangled vegetation, as fast as he could ride. His skill with the machete was incredible. He cut a path for us through the forest. The vines fell to the right and left before his steady strokes; the closed spaces gave way to clearings; the man seemed indefatigable.

The night of April 30 brought us to the Rio Buey, a tributary of the Bayamo River, about twenty miles from the city of Bayamo. Before our hammocks had even swung, Gervacio appeared, his face beaming with satisfaction.

“He’s there, Senor! General Garcia is in Bayamo and the Spanish are retreating down the Cauto River. His rear guard is at Cauto-El-Embarcadero!”

I was so eager to communicate with Garcia that I offered to make the night trip, but after a conference it was decided that nothing would be gained.

May 1, 1898 is “Dewey Day” on our calendar. While sleeping in the jungles of Cuba, the great admiral was trying to find his way past the guns of Corregidor into Manila Bay to destroy the Spanish fleet. On that day, he sank Spanish ships on his way to Garcia and threatened the capital of the Philippines with his cannons.

We set out early that morning. We descended the slope to the plain of Bayamo, terrace by terrace. This great country, devastated for years, seemed to have been uninhabited. We crossed the plain at the black ruins of the hacienda of Candalaria, silent testimony to Spanish warfare. We had traveled more than a hundred miles in one of nature’s most beautiful places, across a tropical garden covered with wild grass, through a wilderness with hardly any human habitation to show for it. We rode through grass so high that it was hidden from view by our arm, through the scorching sun and the scorching heat, but all our discomforts were forgotten at the thought that our destination was near; our mission was almost over. Even our tired horses seemed to share our anticipation and enthusiasm.

At the old Peralejo, where Maceo had attacked General Campos’ column, we entered the royal road leading to Manzanillo-Bayamo and encountered cheerful people in rags and rags, all hurrying towards the city. The chatter of these happy groups reminded me of parrots screaming as they pass through the forests. They were returning to their homes from which they had been expelled.

From Paralejo it was a short journey to the town on the east bank of the river. The town was once a city of 30,000, now a village of perhaps 2,000. It was surrounded on both banks of the stream by a series of block houses built by the Spaniards. These little forts were the first objects seen, and when we came into view they were still prominent with rising flames and smoke. The Cubans had set them on fire when they entered the old metropolis of this once flourishing valley.

We soon lined up on the bank, and after Gervacio and Lopez spoke to the guards, we set off. We stopped in the middle of the river to water our horses and to recharge our batteries for our final run east of the Jucaro-Moron trocha to the officer in charge of Cuba’s military destiny.*

* (I quote from contemporary newspapers: “Cuban generals say that Lieutenant Rowan’s arrival created great enthusiasm in the Cuban army. There was no news of his arrival, and the first time I saw Lieutenant Rowan was when he was galloping down Calle Commercial, with his Cuban guides following him.”)

Within minutes I was in the presence of General Garcia.

The long and arduous journey that involved many risks, chances of failure, and the chance of death was over.

I had made it.

When we arrived in front of General Garcia’s headquarters, the Cuban flag hung lazily on a bent pole over the door. The method of appearing before a man with whom we were accredited on such occasions was new to me. We lined up, got off together, and “mounted.” Gervacio was known to the general, so he advanced to the door and was admitted. He returned shortly afterwards with General Garcia, who greeted me cordially and told me to come in with my aide. The general introduced me to his staff—all in clean white uniforms and with guns at his waist—and explained that the delay was due to the necessary check of my credentials by the Cuban junta in Jamaica, which Gervacio had conveyed to him.

There is humor in everything. In the letters from the junta, I was described as a “trustworthy man.” The translator had made me a “trustworthy man.”

After breakfast we set to work. I explained to General Garcia that my mission was purely military, but that I had left the United States with diplomatic credentials; that the President and the War Department wanted the latest information on the military situation in Eastern Cuba. (Two more officers had been sent to Central and Western Cuba, but they had failed to reach their destination.) Among the matters the United States needed to know were the positions occupied by the Spanish troops; the condition and numbers of the Spanish forces; the character of their officers; especially their commanders; the morale of the Spanish troops; the topography of the country, both local and general; communications, especially the condition of the roads; in short, any information that would enable the American general staff to organize an expedition. Last, but by no means least, General Garcia’s proposals for a joint or separate expedition between the Cuban armies and the United States forces. I also informed him that my government would be happy to receive the same information on the Cuban forces, or as much as the general deemed appropriate. If it did not agree with his plans, I would like to accompany the Cuban forces in the field in such capacity as he deemed appropriate.

General Garcia thought for a moment and then withdrew with his entire staff except his son, Colonel Garcia. Colonel Garcia remained with me. About three o’clock the general returned and said that he had decided to send three officers with me to the United States. These officers were men who had spent their lives in Cuba; they were trained and tried; they all knew the country and could answer all the questions that might be raised in their own special capacity. If I had remained in Cuba for months I could not have prepared so complete a report, and as time was of the essence, the sooner the United States government received the information the better it would be for all concerned.

He went on to explain that his men needed weapons, especially artillery, which was important in the assault on the blockhouses. Ammunition was very scarce, and the many rifles of various calibers used made it difficult to keep an adequate supply. To simplify the matter, he thought it would be better to rearm his men with American rifles.

General Collazo, a famous figure; Colonel Hernandez, and Doctor Vieta, a valuable relative familiar with the general diseases of the island and the tropics; and two sailors, both familiar with the north coast, were to come with us; they might be useful on the return voyage if the United States should decide to furnish the supplies required.

Could I have continued that day — hoy mismo?

Could I ask more questions?

Could I ask more questions? I had been on the move for nine days, over all kinds of terrain. I wished I had had a chance to look around in these strange surroundings, but my response was as quick as his question. I simply replied, “Yes sir!”

Why not? General Garcia, by his quick comprehension and rapid acceptance of the terms, had saved me months of unnecessary trouble and had given my country as much detailed information on the present situation on the island as the Cubans had; certainly as good as that of the enemy.

For the next two hours I was the recipient of an informal welcome. Then at five o’clock a final meal was served, and finally I was told that my escort was at the door. When I reached the street I was surprised not to see my old guide and companion in the column. I asked for Gervacio, and he and the others in the contingent from Jamaica came out. Gervacio wanted to go with me, but Garcia was determined; they were all needed for the service on the south coast, and I would return from the north. I expressed my gratitude to the general for the service of Gervacio and his crew, and the column withdrew from the strong points of the Sierra Maestra. After a real Latin embrace I left and got in. Three cheers were heard as we galloped north.

I had delivered my message to Garcia!

My journey to General Garcia was fraught with danger, but, compared with my return to the United States, it was, far more, an innocent stroll through a beautiful country. There was little to contend with in getting there, for my journey from Jamaica had been over pleasant waters, while on my way to the commandant of Cuba I was well protected and well guided. But war had been declared, and the Spaniards were on the alert. Their soldiers patrolled every mile of coast, their boats every bay and inlet, and the great guns of their forts were ready to speak in equivocal tones to any who violated the rules of war. I was a spy within enemy lines in every respect! Reconnaissance meant death with my face to the wall. Nor had I thought of coming to terms with the furious elements of the sea and air, which were soon to convince me that success was not always a matter of fair sailing.

But the effort had to be made and it had to be successful, or my mission would be fruitless. Its happy ending depended largely on the victorious conduct of the war.

My comrades naturally shared with me the apprehensions that arose, so we proceeded with great caution northward across Cuba, rounding the Spanish positions at Cauto-El-Embarcadero, the head of navigation on the river, at least for warships, until we came to the bottle-shaped port of Manati, where, on the opposite side, a large fort with cannons guarded the entrance.

If only the Spanish soldiers had known of our existence! But perhaps the audacity of our attempt was our salvation. Who could have suspected that an enemy on a mission like ours would choose such a place to mount?

The boat in which we traveled was a sea-shell, “104 cubic feet in capacity.” We had sacks bundled together for sails. Boiled beef and water for rations. We were to sail in this boat, and we did, 150 miles due north to New Providence, Nassau Island. Imagine sailing in such a boat, in hostile waters, patrolled by fast, well-armed lanchas!

But “it must be as the devil wills it!” This was the only way we could fully fulfill our duty.

It was immediately obvious that this boat could not accommodate six men, so Dr. Vieta was sent back to Bayamo with the escort and horses, while five of us prepared to overcome the obstacle of the Spanish cannons and defeat the Spanish warships with a boat not much larger than a rowboat and sack sails!

There was a violent storm at the time we set our departure, and with the waves so strong we could not enter the water. Yet even while waiting there was danger! It was full moon time, and if the clouds cleared with the passing of the storm, our presence could be detected.

But fate was with us!

At 11 o’clock we embarked. There were only five men in the boat, and the boat was in the water. The scattered clouds ran like wild things across the face of the moon, alternately hiding and revealing us, while four of them rowed and a fifth set a course. We could not see the fort as we passed, and perhaps that was the reason we were not seen, but it did not require much imagination to imagine the sullen mouths of the great guns, and we went on working, expecting at every moment to hear a cannon boom and a shot scream. Our little boat tossed and turned like an eggshell, and we were often on the point of capsizing, but our sailors knew the course, our sack sails stood the test, and we were soon making our way “over the trackless green.”

Weary from the unusual exertion, and with nothing to break the monotony of surfing first one wave crest and then another, I fell asleep while sitting upright bravely.

But it did not last long. A huge wave crashed over us, nearly filling our boat with water and nearly capsizing it. From that moment on, no one could sleep. It was bail, bail, bail throughout the long night. Wet with salt water, tired and exhausted, we were happy enough to see the sun peeking through the mist on the horizon.

“Un vapor, Senores!” (a steamboat), shouted the helmsman.

A panic seized every heart. What if it was a Spanish warship? That would mean a short record for all of us.

“Dos vapores, tres vapores, Caramba! doce vapores!” shouted the helmsman, and my companions echoed his cries.

Could it have been the Spanish fleet?

But no, they were Admiral Sampson’s warships, steaming east to attack San Juan del Puerto Rico!

We breathed easier!

All that day we blushed and blushed, blushed and blushed. Yet no one slept or relaxed their anxious gaze. Despite the presence of the United States warships, a gunboat might escape their notice, and if it did, it might overtake and take us prisoner. Night fell upon the five most exhausted men who ever lived. We were almost worn out with fatigue, but rest was impossible for us. With the darkness came the wind again, and with the wind came the heavy waves, and again rope, rope, rope to keep the little ship afloat. The next morning, May 7, about ten o’clock, we saw Curly Keys, at the southern end of the Andros Islands of the Bahamas, and we were glad to go there for a short rest.

That afternoon we overhauled a sponging boat with a crew of thirteen negroes who spoke something strange we did not understand, but sign language is universal, and we soon arranged for a transfer. This boat carried a herd of hogs for food and an accordion. I never want to hear an accordion again. I was exhausted almost to the point of complete exhaustion, and in vain I tried to sleep, but the shrill notes of that instrument prevented me from sleeping.

The next afternoon, as we were rounding the eastern end of New Providence Island, we were captured by the quarantine officials and confined on Hog Island, as the fiction of yellow fever in Cuba gave them an excuse.

However, the next day I informed the American consul-general, Mr. McLean, and he arranged for our release on May 10. On May 11 the boat Fearless approached the pier and we embarked.

When we reached the back of the Florida Keys, luck deserted us. The wind died down and we slept peacefully throughout the day of May 12, but during the night a breeze came up and by the morning of May 13 we were in Key West.

That night we took a train to Tampa and from there we took a train to Washington.

We arrived on time and reported to the Secretary of War, Russel A. Alger, who heard my story and told me to report to General Miles, taking General Garcia’s aides with me. After receiving my report, General Miles wrote to the Secretary of War as follows: “I also recommend that First Lieutenant Andrew S. Rowan, 19th U.S. Infantry Regiment, be promoted to lieutenant colonel of one of the immune regiments. Lieutenant Rowan traveled to Cuba, was with Lieutenant General Garcia in the rebel army, and brought back much valuable information to the government. It was a very dangerous enterprise, and in my judgment Lieutenant Rowan displayed an act of heroism and coolness rarely seen in the history of warfare.”

About a day after my return I attended a cabinet meeting with General Miles, and at the close of the meeting received President McKinley’s congratulations and thanks for the way I conveyed his wishes to General Garcia and the merit of the work.

“You did a very brave thing!” were his last words to me, and they reminded me for the first time that I had done more than my simple duty, that it was a soldier’s duty not to “question why,” but to obey his orders.

I had delivered my message to Garcia.

SOURCE:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Message_to_Garcia

Elbert Hubbard – A Message to Garcia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elbert_Hubbard

What is AGI?

https://aws.amazon.com/tr/what-is/artificial-general-intelligence/

Willow

https://blog.google/technology/research/google-willow-quantum-chip/

Google Quantum AI

https://www.youtube.com/@GoogleQuantumAI

OpenAI

Youtube: OpenAI – https://www.youtube.com/@OpenAI

X site: https://x.com/openai

NVIDIA:

https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/solutions/ai/

CEO Jensen Huang: https://x.com/thejesenhuang